Consider a forgotten game in April 2010 between the Cleveland Indians and the Chicago White Sox. The White Sox were up a run with two outs in the eighth. Their set-up man, Matt Thornton, was on the mound, protecting a lead with a runner on first and the right-handed Jhonny Peralta at bat. Ahead in the count with one ball and two strikes, Thornton froze Peralta with a slider on the outside half of the plate, a couple inches below the belt. For a pitch like that, the umpire, Bruce Dreckman, would normally call a strike — 80 percent of the time, the data shows. But in two-strike counts like Peralta’s, he calls a strike less than half the time.

Sure enough, that night Dreckman called a ball. Two pitches later, Peralta lashed a double to right, scoring the runner and tying the game. Neither team scored again until the 11th, when Cleveland scored twice to win the game. Had Peralta struck out to end the top of the eighth, Chicago almost certainly would have won.

This one call illustrates a statistical regularity: Umpires are biased. About once a game, an at-bat ends in something other than a strikeout even when a third strike should have been called. Umpires want to make the right call, but they also don’t want to make the wrong call at the wrong time. Ironically, this prompts them to make bad calls more often.

That’s according to research I did with David P. Daniels showing that the strike zone changes when the stakes are highest. We looked at more than 1 million pitches, almost all ball and strike calls from the 2009, 2010 and 2011 regular seasons, and found that the strike zone expands in three-ball counts and shrinks in two-strike counts.

The umpire’s job is simple: Call a strike when the pitch crosses the official strike zone; call a ball when it doesn’t. When the right call is obvious, umpires make it almost every time. One way to see this is to look at the probability of a called strike by pitch location.

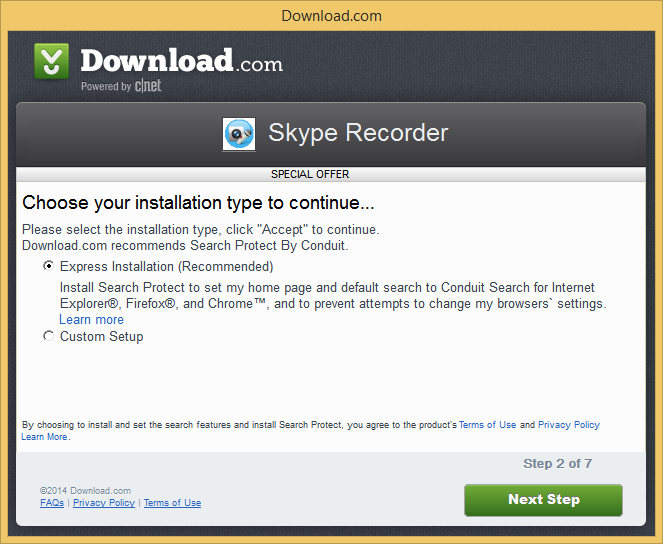

Probability of a Called Strike

The plane at the bottom of the figure is the plane that rises from the front of home plate — the same one on which the official strike zone is occasionally rendered in television replays. The thick red lines on the axes denote the strike zone. The red on the horizontal axis is the width of home plate; the red on the vertical axis is the normalized distance between the batter’s chest and the bottom of his knees.

The 3D heat map rising from the plane measures the probability of a called strike at each location on the plane. Home-plate umpires are good at calling the obvious. Pitches that travel right down the center of the official strike zone — through the red at the top of the heat map — are called strikes more than 99 percent of the time. Pitches that cross the plane well outside the official strike zone — where the heat map is its deepest blue — are called strikes less than 1 percent of the time.

Umpires are inconsistent at the edges of the official strike zone, where the heat map turns green. Here, pitches that cross the plane in the same location are sometimes called strikes and sometimes called balls. This band of uncertainty is wide: about six to eight inches separate pitches that are called strikes 90 percent of the time and pitches that are called balls 90 percent of the time.

There’s a difference between an umpire being inconsistent and an umpire being biased. Inconsistency usually takes place within that band of uncertainty, when the umpire makes different calls on pitches at the same location. But he is biased when those differences correlate with factors other than pitch location, like the count. Where umpires are inconsistent, they also happen to be biased. To see this, consider two versions of the figure above: one for when the count has three balls, and one for when the count has fewer than three balls. These heat maps should be the same. Whether there are three balls in the count shouldn’t matter. All that should matter is the location of the pitch.

When we look at the difference between these two heat maps, we should see no difference — a flat plane. But we don’t. We see an expansion of the strike zone in three-ball counts.

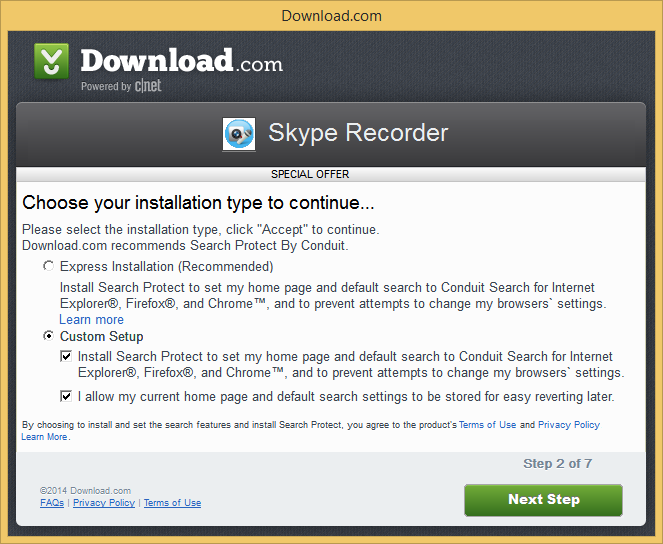

Change in the Probability of a Called Strike With Three Balls

The official strike zone is the red rectangle beneath the heat map. The color and height of the heat map measure the change in the probability of a called strike when the count has three balls versus when there are two or fewer balls. The deep blue signifies no change — these are the pitches that are so obviously a ball or strike that not even a three-ball count changes them. In the center of the official strike zone, obvious strikes are still strikes; on the periphery, obvious balls are still balls. But on the edge of the official strike zone — in the band of uncertainty — a ring of mountains rises from the plane. The strike zone expands in three-ball counts, particularly at the top and bottom of the zone’s vertical axis. Borderline pitches, which are normally called strikes 50 percent of the time, are called strikes about 60 percent of the time with three balls in the count. Umpires act as if they would rather keep an at-bat going on a borderline pitch than issue a walk.

In two-strike counts, we see the inverse effect. For close pitches, a strike is now less likely to be called, which makes our heat map look like a moat.

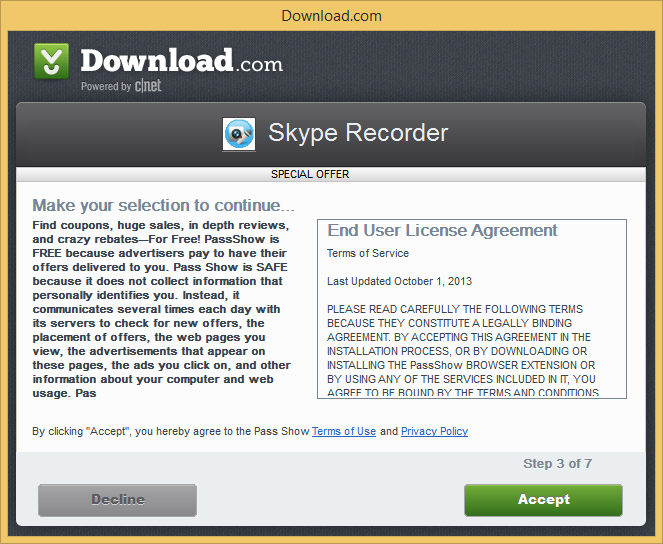

Change in the Probability of a Called Strike With Two Strikes

The strike zone shrinks by as much as 20 percentage points in the top and bottom. With two strikes, borderline pitches — those that are ordinarily 50/50 calls — become 30/70 calls (30 percent strikes, 70 percent balls) for the average umpire. And with two strikes, the most biased umpire calls balls on borderline pitches almost every time. On close calls, umpires act as if they would rather give the batter another chance than call a third strike.

In both maps, the biases are greatest where the boundaries of the official strike zone are least apparent. What matters most is the vertical location of the pitch. Standing behind the plate, the umpire can easily tell whether a pitch is too far inside or outside. But it’s harder to know where the pitch is relative to the batter’s knees and chest. We would expect this uncertainty to breed inconsistency. But it also seems to induce the greatest bias. The highest peaks and the deepest parts of the moat are at the top and bottom of the strike zone.

Finally, we see that the strike zone shrinks again when the previous pitch in the at-bat was a called strike.

Change in the Probability of a Called Strike When the Previous Pitch Was a Called Strike

Here, the shrinkage is more uniform — about the same on the sides as on the top and bottom. The blue tips of the moat are about 15 percentage points deep: 50/50 calls become 35/65 calls when the last pitch in the at-bat was a called strike. Umpires appear reluctant not only to end the at-bat but also to call two strikes in a row. (Interestingly, there is no change in the probability of a called strike when the last pitch was called a ball.)

These mistakes are frequent — pitchers tend to pitch to the borders of the official strike zone. And they are consequential — they happen in the most pivotal calls. When a 50/50 call becomes a 60/40 call, as it does with three balls, umpires are mistakenly calling strikes on 10 percent of borderline pitches. When a 50/50 call becomes a 30/70 call, as it does with two strikes, umpires are mistakenly calling balls on 20 percent of borderline pitches.

Major League Baseball has embraced technologies that are meant to make calls on the field more consistent. The league has long used pitch-tracking technology to encourage home-plate umpires to behave more like machines, evidently without complete success. This past offseason, the MLB extended replay review to cover essentially all umpire decisions — except ball and strike calls. Now as before, no justice will be served when a pitcher throws a strike and the umpire drops the ball.

This article is adapted from “What “What Does it Take to Call a Strike? Three Biases in Umpire Decision Making,” which the author wrote with David P. Daniels.